Homeostasis

Homeostasis is the ability of the body to maintain relative stability and function even though drastic changes may take place in the external environment or in one portion of the body. A series of control mechanisms, some functioning at the organ or tissue level and other centrally controlled, maintain homeostasis. The major central homeostatic controls are the nervous and endocrine systems.

Physical and mental stresses, injury, and disease continually challenge us and any of them can interfere with homeostasis. When the body loses its homeostasis, it may plunge out of control, into dysfunction, illness, and even death. Homeostasis at the tissue, organ, organ system, and organism levels reflects the combined and coordinated actions of many cells. Each cell contributes to maintaining homeostasis.

Maintaining Homeostasis

To maintain homeostasis, the body reacts to an abnormal change (induced by a toxic substance, biological organism, or other stress) and makes certain adjustments to counter the change (a defense mechanism). The primary components responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis include:

Example: Reaction to a Toxin

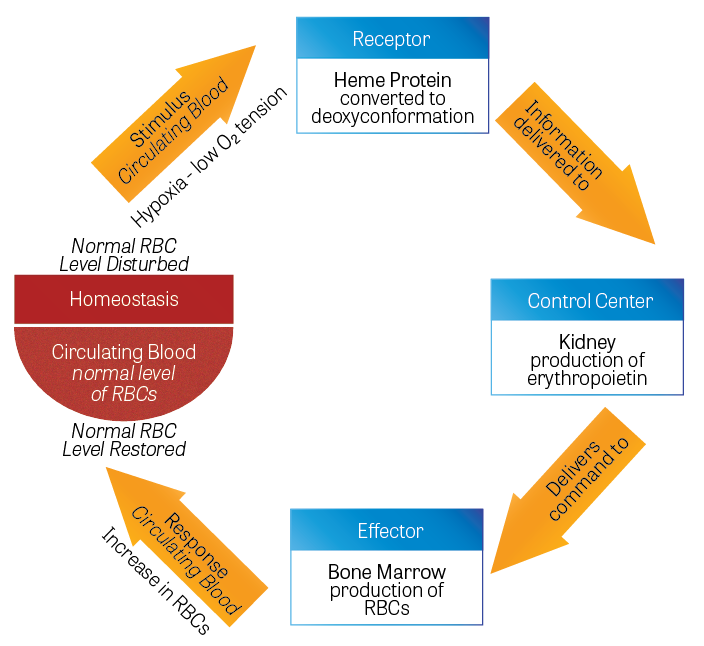

An example of a homeostatic mechanism can be illustrated by the body's reaction to a toxin that causes anemia and hypoxia (low tissue oxygen) (Figure 1). The production of red blood cells (erythropoiesis) is controlled primarily by the hormone, erythropoietin. When the body goes into a state of hypoxia (the stimulus), it prompts the heme protein (the receptor) that signals the kidney to produce erythropoietin (the effector). This, in turn, stimulates the bone marrow to increase red blood cells and hemoglobin, raising the ability of the blood to transport oxygen and thus raises the tissue oxygen levels in the blood and other tissues. This rise in tissue oxygen levels serves to suppress further erythropoietin synthesis (feedback mechanism). In this example, cells and chemicals interact to produce changes that can either disturb homeostasis or restore homeostasis. Toxic substances that damage the kidney can interfere with the production of erythropoietin or toxic substances that damage the bone marrow can prevent the production of red blood cells. This interferes with the homeostatic mechanism described resulting in anemia.

Physical and mental stresses, injury, and disease continually challenge us and any of them can interfere with homeostasis. When the body loses its homeostasis, it may plunge out of control, into dysfunction, illness, and even death. Homeostasis at the tissue, organ, organ system, and organism levels reflects the combined and coordinated actions of many cells. Each cell contributes to maintaining homeostasis.

Maintaining Homeostasis

To maintain homeostasis, the body reacts to an abnormal change (induced by a toxic substance, biological organism, or other stress) and makes certain adjustments to counter the change (a defense mechanism). The primary components responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis include:

- Stimulus — a change in the environment, such as an irritant, loss of blood, or presence of a foreign chemical.

- Receptor — the site within the body that detects or receives the stimulus, senses the change from normal, and sends signals to the control center.

- Control center — the operational point at which the signals are received, analyzed, and an appropriate response is determined. This is sometimes referred to as the integration center since it integrates the signals with other information to determine if a response is needed and the nature of a response.

- Effector — the body site where a response is generated, which counters the initial stimulus and thus attempts to maintain homeostasis.

- Feedback mechanisms — methods by which the body regulates the degree of response that has been elicited. A negative feedback depresses the stimulus to shut off or reduce the effector response, whereas a positive feedback has the effect of increasing the effector response.

Example: Reaction to a Toxin

An example of a homeostatic mechanism can be illustrated by the body's reaction to a toxin that causes anemia and hypoxia (low tissue oxygen) (Figure 1). The production of red blood cells (erythropoiesis) is controlled primarily by the hormone, erythropoietin. When the body goes into a state of hypoxia (the stimulus), it prompts the heme protein (the receptor) that signals the kidney to produce erythropoietin (the effector). This, in turn, stimulates the bone marrow to increase red blood cells and hemoglobin, raising the ability of the blood to transport oxygen and thus raises the tissue oxygen levels in the blood and other tissues. This rise in tissue oxygen levels serves to suppress further erythropoietin synthesis (feedback mechanism). In this example, cells and chemicals interact to produce changes that can either disturb homeostasis or restore homeostasis. Toxic substances that damage the kidney can interfere with the production of erythropoietin or toxic substances that damage the bone marrow can prevent the production of red blood cells. This interferes with the homeostatic mechanism described resulting in anemia.

Figure 1. Homeostatic mechanism to restore levels of red blood cells

(Image Source: NLM)

(Image Source: NLM)

Knowledge Check (Solutions on next page)

1) The ability of the body to maintain relative stability and function even though drastic changes may take place in the external environment or in one portion of the body is known as:

a) Physiology

b) Homeostasis

c) Toxicity

2) To maintain homeostasis, the body reacts to an abnormal change (induced by a toxin, biological organism, or other stress) and makes certain adjustments to counter the change (a defense mechanism). The component of the homeostasis process which detects the change in the environment is known as the:

a) Effector

b) Stimulus

c) Receptor